꾸지뽕나무 잎과 우슬 복합물의 골 질환 개선 소재 개발가능성에 대한 연구

Ⓒ The Society of Pathology in Korean Medicine, The Physiological Society of Korean Medicine

Abstract

This study was conducted to suggest the Cudrania tricuspidata leaf and Achyranthes japonica Nakai Complex (CAC) possibility of use as a functional natural material for improving bone disease. Cudrania tricuspidata leaf and Achyranthes japonica Nakai were mixed in the same amount, extracted with hot water, and then powdered and used in the study. After, the cytotoxicity of CAC for osteoblasts (MG63 cell), osteoclasts (differentiated RAW264.7 cell), and macrophages (RAW264.7 cell) were evaluated by MTT assay, and ALP assay and TRAP assay were performed to confirm the differentiation capacity of osteoblasts and osteoclasts, respectively. In addition, the anti-inflammatory effect in macrophages was evaluated by ELISA, qRT-PCR, and western blot assay. CAC did not proliferated osteoblasts and osteoclasts, but increased ALP activity against osteoblasts differentiation and decreased TRAP activity against osteoclasts differentiation. CAC did not proliferated macrophages but decreased nitric oxide production. Also, decreased NOS2, IL1B, IL6, PTGS2, and TNFA gene expression, and JNK and p38 protein phosphorylation in a concentration-dependent manner, but ERK protein phosphorylation was not changed. As a result, CAC increased the differentiation and activation of osteoblasts, inhibited the differentiation and activation of osteoclasts, and regulated the expression of inflammatory cytokines in macrophages. Therefore, it is thought that CAC can be used as a functional natural material that prevents bone disease and has an anti-inflammatory effect.

Keywords:

Cudrania tricuspidata, Achyranthes japonica Nakai, Inflammatory, Bone metabolism, Osteoarthritis서 론

뼈의 재형성과 유지 및 관리는 조골세포(Osteoblasts)에 의한 새로운 뼈의 형성과 파골세포(Osteoclasts)에 의한 뼈의 지속적인 재흡수를 통해 진행되며, 뼈 조직은 수산화인회석(Hydroxyapatite)을 중심으로 칼슘과 인산염이 결합되어 골격을 형성하는 콜라겐 섬유로 구성된다1). 이러한 조골세포와 파골세포는 항상성을 유지하고 있으며, 이 상태는 활성화, 재흡수, 역전, 형성의 4 단계가 순차적으로 진행되고 이러한 조골세포와 파골세포의 균형이 파괴되면 다양한 골 질환의 원인이 된다2).

퇴행성 골관절염(Osteoarthritis)은 연골의 퇴화 및 소실, 활액 염증, 연골 및 골 경화증을 동반한 관절 주위 뼈의 변화를 특징으로 하는 만성 골 질환이다3,4). 또다른 골 질환 중 한가지인 골다공증은 낮은 골밀도와 뼈를 구성하는 미세구조의 파괴를 바탕으로 뼈의 강도가 감소하는 질환이다5). 이러한 퇴행성 골관절염과 골다공증은 생활습관, 노화, 에스트로겐 결핍 등과 같은 다양한 요인에 의해 발병된다고 알려져 있으며, 고령사회로 진입한 현재 사회적 문제로 대두되고 있다6,7).

현재 골 질환의 치료에는 소염진통제, 스테로이드성 치료제, 비스포스포네이트, 칼시토닌과 같은 화합물들을 사용하고 있으며, 치료 및 개선 효과 대비 부작용이 더 크게 나타나기 때문에, 화합물에 비해 상대적으로 부작용이 적은 천연물 및 천연물 유래 성분을 사용한 연구가 다양하게 진행되고 있다8-10).

꾸지뽕나무(Cudrania tricuspidata)는 뽕나무과에 속하는 낙엽교목으로 한국, 일본, 중국 등 동아시아에 주로 자생하며, 열매, 잎, 뿌리, 줄기등은 한약재로써 염증성 질환에 사용되어 왔다11-13). 현재 진행된 연구로는 꾸지뽕나무 열매에서 유래된 플라보노이드의 산화질소 억제 효과14) 및 열매 추출물의 신경세포 보호능15), 아토피피부염 개선16), 지방 흡수 및 비만에 대한 효과17,18)에 대한 연구가 진행되었으며, 뿌리 및 껍질을 사용한 항산화 효과19), 염증 개선20), 죽상동맥경화증 개선21)에 대한 연구가 진행되었다. 하지만 잎을 사용한 연구로는 췌장 리파아제 활성 및 체내 지질 흡수에 대한 연구22)와 HPLC 분석을 통한 꾸지뽕나무 잎에 존재하는 항산화 물질에 대한 연구23)가 진행되었다.

우슬(Achyranthes japonica Nakai)은 비름과에 속하는 다년생 초본식물인 쇠무릎의 뿌리부분으로 꾸지뽕나무와 동일하게 동아시아에 주로 자생하며, 골관절염 및 통증 개선을 위한 한약재로써 사용되어왔다24-26). 이는 saponin, triterpenoids, phytoecdysteroid, inokosterone 등 골 질환에 효과적인 화학성분을 함유하고 있으며25,26), 항균작용27), 류마티스 관절염28), 항염증29,30), 항산화31)에 대한 연구가 진행되었다.

따라서 본 연구에서는 꾸지뽕나무 잎과 우슬 복합물(Cudrania tricuspidata Leaf and Achyranthes japonica Nakai Complex, CAC)을 처리하여 조골세포의 alkaline phosphate(ALP) 활성과 파골세포의 tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase(TRAP) 활성에 대한 유의적인 효능을 확인하였으며, 대식세포에서의 염증 개선 효능에 대한 유의적인 결과를 얻었기에 이를 보고하여 골 질환 개선 소재로써 꾸지뽕나무 잎과 우슬 복합물의 사용가능성을 제시하고자 한다.

재료 및 방법

1. 시료 추출

꾸지뽕나무 잎은 충남 금산의 홍익약초영농법인에서 공급받았고 우슬은 국내에서 재배되었으며, 옴니허브에서 구입하여 사용하였다. 꾸지뽕나무 잎과 우슬 각 25 g에 500 ml의 증류수를 넣어 100℃에서 3시간 추출하였다. 추출물을 여과지로 여과한 후, rotary vacuum evaporator(BÜCHI Labortechnik AG, Switzerland)를 통해 감압농축하고 freeze dryer(ilShinbiobase, Korea)를 통해 동결건조를 진행하여 14.8 g의 분말(수득률: 29.6%)을 얻었으며, -20℃에 보관하면서 사용하였다.

2. 조골세포 배양

인간 유래 조골세포인 MG-63세포는10% fetal bovine serum(Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA)과 1% penicillin-streptomycin(Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA)으로 구성된 RPMI-1640 media(Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA)를 사용하여 37℃, 5% CO2 조건이 유지되는 세포배양기에서 배양하였다. 세포는 2~3일 주기로 계대배양하고 분화 유도를 위해 10 mM의 β-glycerophosphate(Sigma-Aldrich, USA)와 50 mg/ml의 ascorbic acid(Sigma-Aldrich, USA)를 첨가하였으며, media는 3일 간격으로 교체하였다.

3. 파골세포 배양

마우스 대식세포인 RAW264.7 세포는 10% fetal bovine serum(Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA)과 1% penicillin-streptomycin(Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA)으로 구성된 DMEM(Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA)을 사용하여 37℃, 5% CO2 조건이 유지되는 세포배양기에서 배양하였다. 세포는 2~3일 주기로 계대배양하고 분화 유도를 위해 50 ng/ml의 receptor activator of nuclear factor kappa-B ligand(RANKL; Sigma-Aldrich, USA)과 25 ng/ml의 macrophage colony-stimulating factor(M-CSF; Sigma-Aldrich, USA)를 첨가하였으며, media는 3일 간격으로 교체하였다.

4. 대식세포 배양

마우스 대식세포인 RAW264.7 세포는 10% fetal bovine serum(Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA)과 1% penicillin-streptomycin(Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA)으로 구성된 DMEM(Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA)을 사용하여 37℃, 5% CO2 조건이 유지되는 세포배양기에서 배양하였다. 세포는 2~3일 주기로 계대배양하여 실험에 사용하였다.

5. 세포생존율 측정

조골세포, 파골세포 및 대식세포를 각각 96 well plate에 1×104 cells/well로 분주하여 24시간 배양하였다. 배양 후, CAC를 50, 100, 200, 400 ug/ml의 농도로 처리하고 다시 24시간 배양하였으며, 10 ul의 EZ-Cytox solution(Daeilab, Korea)을 추가하고 세포배양기에서 30분간 반응시켰다. 반응 후 450 nm에서 흡광도를 측정하여 세포생존율을 계산하였다.

6. ALP 활성

MG-63 세포를 96 well plate에 5×103 cells/well로 분주하여 24시간 배양하였다. 24시간 후 분화유도배지로 교환하고 CAC를 50, 100, 200 ug/ml의 농도로 처리하여 4일 동안 배양한 뒤 배양액을 제거하고 PBS로 세척하였다. 0.1 % Triton X-100(Sigma-Aldrich, USA) 20 ul를 넣어 37℃에서 30분간 용해시키고 100 mM p-nitrophenyl phosphate(pNPP; Sigma-Aldrich, USA) 100 ul를 추가한 후 37 ℃에서 30분간 반응시켰다. 반응 후 1 M NaOH(Sigma-Aldrich, USA) 100 ul를 넣어 반응을 정지시키고 405 nm에서 흡광도를 측정하여 ALP 활성을 계산하였다.

7. TRAP 활성

RAW264.7 세포를 96 well plate에 5×103 cells/well로 분주하여 24시간 배양하였다. 24시간 후 분화유도배지로 교환하고 CAC를 50, 100, 200 ug/ml의 농도로 처리하여 4일 동안 배양한 뒤 배양액을 제거하고 PBS로 세척하였다. 4% formaldehyde(Sigma-Aldrich, USA)로 세포를 고정하고 500 mM p-nitrophenyl phosphate(Sigma-Aldrich, USA)와 10 mM tartrate(Sigma-Aldrich, USA)를 포함하는 50 mM citrate buffer(pH 4.6)를 고정한 세포에 100 ul씩 분주하여 37℃에서 30분간 반응시켰다. 반응 후 1 M NaOH(Sigma-Aldrich, USA) 100 ul를 넣어 반응을 정지시키고 405 nm에서 흡광도를 측정하여 TRAP 활성을 계산하였다.

8. Nitric oxide 생성량 측정

NO assay kit(iNtRON Biotechnology, Korea)를 사용하여 NO 생성량을 측정하였다. RAW264.7 세포를 24 well plate에 4×104 cells/welll로 분주하여 24시간 배양하고 50, 100, 200 ug/ml 농도의 CAC를 처리하고, 2시간 후 100 ng/ml의 lipopolysaccharide(LPS; Sigma-Aldrich, USA)를 추가하여 18시간 배양하였다. 배양 후 세포배양액 100 ul에 N1 buffer 50 ul를 추가하여 상온에서 10분간 반응시키고 N2 buffer 50 ul를 추가하여 상온에서 10분간 반응시켰다. 반응 후 540 nm에서 흡광도를 측정하여 standard curve에 준하여 NO 생성량을 계산하였다.

9. 유전자 발현량 측정

RAW264.7 세포를 6 well plate에 2×105 cells/welll로 분주하여 24시간 배양하고 50, 100, 200 ug/ml 농도의 CAC를 처리하고, 2시간 후 100 ng/ml의 LPS를 추가하여 18시간 배양하였다. 배양 후 원심분리하여 침전 시킨 세포는 total RNA extraction kit(iNtRON Biotechnology, Korea)를 사용하여 RNA를 추출하고 cycle script RT premix(Bioneer, Korea)를 사용하여 cDNA로 합성하였다. Rotor-Gene 6000(QIAGEN, Germany) 장비와 SYBR Green RT-PCR Kit(QIAGEN, Germany)를 사용하여 initial activation step(95℃ 5분) 1회, cycling step(95℃ 5초, 60℃ 10초)를 40회 수행하였으며, housekeeping gene인beta-actin(ACTB)의 발현량을 바탕으로 각 유전자 발현량을 계산하였다. 본 연구에서 사용한 primer들의 정보는 Table 1에 표기하였다.

10. 단백질 발현량 측정

RAW264.7 세포를 6 well plate에 2×105 cells/welll로 분주하여 24시간 배양하고 50, 100, 200 ug/ml 농도의 CAC를 처리하고, 2시간 후 100 ng/ml의 LPS를 추가하여 18시간 배양하였다. 배양 후 원심분리하여 침전 시킨 세포는 RIPA buffer(Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA)와 protease 및 phosphatase Inhibitor cocktail(Sigma-Aldrich, USA) 혼합 용액을 사용하여 단백질을 추출하였으며, BCA protein assay kit(Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA)로 정량하여 전기영동하였다. 이 후, PVDF membrane에 단백질을 transfer시키고 primary antibody를 4℃에서 18시간 반응시켰으며, membrane을 세척하여 secondary antibody를 상온에서 1시간 반응시켰다. 다시 membrane을 세척하고 ECL solution(iNtRON Biotechnology, Korea)을 처리하여 chemidoc fusion FX(Vilber Lourmat, France)로 단백질 발현량을 확인하였다.

11. 통계처리

모든 실험 결과는 mean±standard deviation으로 나타내었으며, SPSS Statistics Version 21.0 (IBM, New York, United States) 통계프로그램을 이용하였다. 두 그룹 간의 통계적 비교는 independent sample t-test를 사용하여 수행하였고 여러 그룹 간의 통계적 비교는 one-way ANOVA를 사용하여 수행하였으며, 마지막으로 tukey’s range test를 통해 p<0.05 수준에서 유의성을 사후 검정하였다.

결 과

1. 세포독성 측정

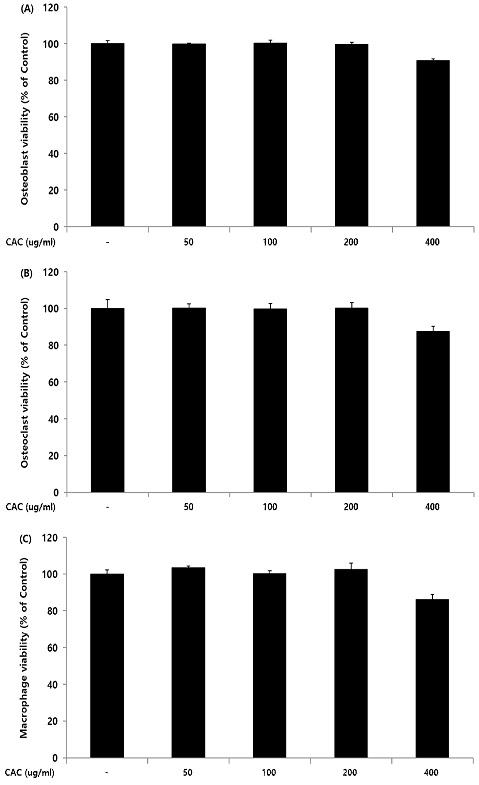

조골세포, 파골세포, 대식세포에서 CAC의 세포독성 여부를 확인하기위해 cell viability assay를 진행하였으며, CAC를 처리하지 않은 control그룹을 100%의 세포생존율로 설정하고 이와 비교하여 CAC의 세포독성 여부를 확인하였다. 확인 결과, CAC는 50, 100, 200 ug/ml 농도에서 control그룹과 차이가 나타나지 않았으나 400 ug/ml 농도에서는 조골세포, 파골세포 및 대식세포 모두에서 control그룹에 비해 10% 이상의 세포생존율을 감소시켰다. 이 결과는 CAC가 200 ug/ml 이하의 농도에서는 세포독성이 나타나지 않음을 확인할 수 있다(Fig. 1).

Cytotoxicity of CAC on osteoblast, osteoclast, and macrophage. Each cell were treated with 50, 100, 200, and 400 ug/ml of CAC for 24 h. Cytotoxicity was determined by measuring cell viability. Data represented the mean±standard deviation of three independent experiments. A; osteoblast viability, B; osteoclast viability, C; macrophage viability.

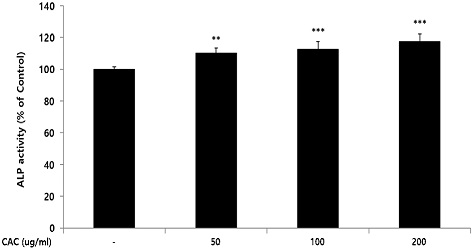

2. ALP 활성 증가

조골세포의 활성에 CAC가 미치는 영향을 확인하기 위해 ALP activity assay를 진행하였으며, CAC를 처리하지 않은 control그룹을 100%의 ALP 활성으로 설정하고 이와 비교하여 CAC가 ALP 활성에 미치는 영향을 확인하였다. 확인 결과, CAC는 50, 100, 200 ug/ml 농도에서 control그룹에 비해 농도의존적이고 유의적인 ALP 활성의 증가가 나타났다(Fig. 2).

Effect of CAC on ALP activity in osteoblast. After MG-63 cells were differentiated into osteoblasts, they were treated with 50, 100, and 200 ug/ml of CAC for 4 days. ALP activity was measured by the spectrophotometry method using p-nitrophenyl phosphate as a substrate. Data represented the mean±standard deviation of three independent experiments(Significance of results, **: p<0.01, ***: p<0.001 compared to control).

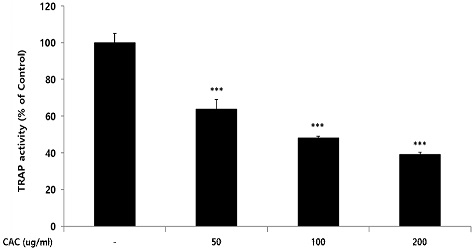

3. TRAP 활성 감소

파골세포의 활성에 CAC가 미치는 영향을 확인하기 위해 TRAP activity assay를 진행하였으며, CAC를 처리하지 않은 control그룹을 100%의 TRAP 활성으로 설정하고 이와 비교하여 CAC가 TRAP 활성에 미치는 영향을 확인하였다. 확인 결과, CAC는 50, 100, 200 ug/ml 농도에서 control그룹에 비해 농도의존적이고 유의적인 TRAP 활성의 감소가 나타났다(Fig. 3).

Effect of CAC on TRAP activity in osteoclast. After RAW264.7 cells were differentiated into osteoclasts, they were treated with 50, 100, and 200 ug/ml of CAC for 4 days. TRAP activity was measured by the spectrophotometry method using p-nitrophenyl phosphate and tartrate as a substrate. Data represented the mean±standard deviation of three independent experiments(Significance of results, ***: p<0.001 compared to control).

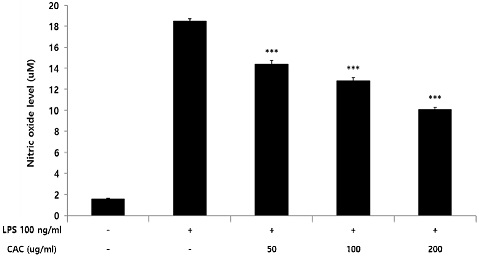

4. Nitric oxide 생성량 감소

Nitric oxide 생성량에 CAC가 미치는 영향을 확인하기 위해 griess assay를 진행하였으며, LPS를 처리하여 대식세포의 염증반응을 유도하고 CAC를 처리하지 않은 control 그룹과 비교하여 CAC가 nitric oxide 생성량에 미치는 영향을 확인하였다. 확인 결과, CAC는 50, 100, 200 ug/ml 농도에서 control그룹에 비해 농도의존적이고 유의적인 nitric oxide 생성량의 감소가 나타났다(Fig. 4).

Effect of CAC on nitric oxide level in LPS-induced macrophage. RAW264.7 cells were pretreated with 50, 100, and 200 ug/ml of CAC for 2 h, and treated 100 ng/ml LPS for 18 h. Nitric oxide level was measured by the spectrophotometry method using nitrate as a substrate. Data represented the mean±standard deviation of three independent experiments(Significance of results, ***: p<0.001 compared to control).

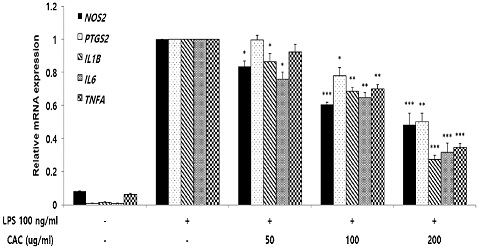

5. 염증성 사이토카인 유전자 발현량 감소

염증성 사이토카인 유전자 발현량에CAC가 미치는 영향을 확인하기 위해 qRT-PCR를 진행하였으며, LPS를 처리하여 대식세포의 염증반응을 유도하고 CAC를 처리하지 않은 control 그룹과 비교하여 CAC의 효능을 확인하였다. 확인 결과, CAC는 50, 100, 200 ug/ml 농도에서 NOS2, IL1B, IL6 유전자 발현량을 감소시켰고 100과 200 ug/ml 농도에서 PTGS2, TNFA 유전자 발현량을 감소시켰으며, 이들은 모두 control그룹에 비해 농도의존적이고 유의적인 결과로 도출되었다(Fig. 5).

Effect of CAC on inflammatory cytokine mRNA expression in LPS-induced macrophage. RAW264.7 cells were pretreated with 50, 100, and 200 ug/ml of CAC for 2 h, and treated 100 ng/ml LPS for 18 h. An inflammatory cytokine mRNA expression was measured by the qRT-PCR method. Data represented the mean±standard deviation of three independent experiments(Significance of results, *: p<0.05, **: p<0.01, ***: p<0.001 compared to control).

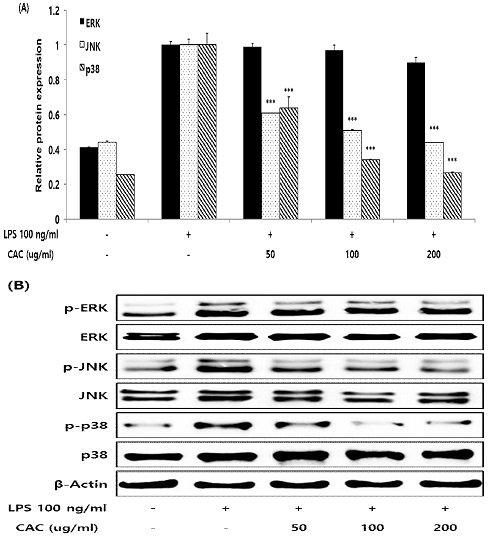

6. MAPKs 신호전달인자 인산화 감소

유전자 발현을 조절하는 상위 단계인 MAPKs 신호전달인자 인산화에 CAC가 미치는 영향을 확인하기 위해 western blot 을 진행하였으며, LPS를 처리하여 대식세포의 염증반응을 유도하고 CAC를 처리하지 않은 control 그룹과 비교하여 CAC의 효능을 확인하였다. 확인 결과, CAC는 ERK의 인산화를 변화시키지 못하였으나 50, 100, 200 ug/ml 농도에서 JNK와 P38의 인산화를 감소시켰으며, 이들은 control그룹에 비해 농도의존적이고 유의적인 결과로 도출되었다(Fig. 6).

Effect of CAC on MAPKs pathway protein expression in LPS-induced macrophage. RAW264.7 cells were pretreated with 50, 100, and 200 ug/ml of CAC for 2 h, and treated 100 ng/ml LPS for 18 h. MAPKs pathway protein expression was measured by the western blot method. Data represented the mean±standard deviation of three independent experiments(Significance of results, ***: p<0.001 compared to control). A; Bar graph data of MAPKs pathway protein expression, B; Band image data of MAPKs pathway protein expression.

고 찰

인체 내 뼈는 노화 및 손상된 골 조직이 파괴되는 골 흡수(bone resorption) 과정과 새로운 골 조직이 생성되는 골 형성(bone formation) 과정의 균형을 통해 우리 몸의 형태를 유지하고 장기를 보호한다32,33). 뼈의 항상성을 유지하는 두 세포 사이의 균형이 무너지게 되면 조골세포의 과도한 활성화에 의한 골 경화증(osteosclerosis)이나 파골세포의 과도한 활성화에 의한 골다공증(osteoporosis)과 같은 질환이 발생하며, 류마티스 및 골 관절염과 같은 염증 반응을 통해 조골세포와 파골세포의 균형이 붕괴된다34). 따라서 다양한 골 질환의 예방 및 치료를 위해 골 대사 및 항염증에 효과적인 소재 발굴에 대한 연구가 다양하게 이루어지고 있다.

이에 본 연구에서는 항염증 효능이 우수한 꾸지뽕나무 잎과 골 질환에 효과적인 우슬 혼합물이 조골세포와 파골세포의 활성에 미치는 영향을 확인하고 대식세포에서의 염증 개선 효과를 구명하여 골 질환 개선 천연물 소재로써 활용가능성을 제시하고자 하였다.

골 조직을 합성하는 조골세포는 연골세포, 지방세포, 근육세포, 섬유아세포등 다양한 세포로 분화할 수 있는 기질세포인 중간엽 줄기세포에서 유래된 세포로서 세포막에 alkaline phosphate(ALP)가 존재하며35), 이 효소는 석회화가 진행되고 있는 조직의 기질 소포에서 높게 발현되고 이러한 특징을 통해 골 세포 분화의 지표인자로써 사용되고 있다36,37). 본 연구에서 꾸지뽕나무 잎과 우슬 복합물은 조골세포의 증식을 유도하지는 못하였으며, 200 ug/ml 이하의 농도에서는 세포에 대한 독성이 나타나지 않았다. 또한 골 세포 분화의 지표인자인 ALP 활성을 농도의존적으로 증가시켰으며, 이러한 결과는 꾸지뽕나무 잎과 우슬 복합물이 조골세포의 분화 및 골 형성에 대한 기능성 소재로써 사용가능성을 나타내고 있다(Fig. 1A, 2).

골 조직을 파괴하는 파골세포는 단핵구/대식세포 계통의 다핵 세포이며, 조혈 모세포에서 파골세포 전구체로 전환되고 receptor activator of nuclear factor kappa-B ligand(RANKL) 및 macrophage colony-stimulating factor(M-CSF)와 같은 화학 주성 인자들에 의해 성숙된 파골세포로의 분화가 유도된다33,38,39). 파골세포는 여러 단계를 거쳐 분화가 이루어지며, 먼저 RANKL과 결합하여 tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase(TRAP) 양성세포로 분화되고 interleukin-1, tumor necrosis factor-α(TNF-α)와 같은 염증성 인자로 자극되어 세포와 세포가 융합된 TRAP 양성 다핵세포로 분화된다. 따라서 파골세포 분화의 지표인자로써 TRAP 활성이 사용되고 있다39,40). 꾸지뽕나무 잎과 우슬 복합물은 400 ug/ml이상의 농도에서 파골세포의 증식을 억제하였으며, 파골세포 분화의 지표인자인TRAP 활성을 농도의존적으로 감소시켰다. 해당 결과를 통해 꾸지뽕나무 잎과 우슬 복합물이 파골세포의 증식과 분화를 억제한다는 것을 확인할 수 있다(Fig. 1B, 3).

염증반응은 외상 및 감염에 대하여 필수적인 조직반응으로 reactive oxygen species(ROS), nitric oxide(NO)와 같은 화합물 및 interleukin 1 beta(IL-1β), tumor necrosis factor alpha(TNF-α)와 같은 염증성 사이토카인들의 생합성으로 시작되며, 이러한 염증반응이 지속될 경우 조직의 손상을 유도하거나 만성 염증성 질환의 원인이 되기 때문에 반응 지속시간을 조절해야 한다41,42). 이러한 염증반응은 janus kinase-signal transducer and activator of transcription(JAK-STAT), nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells(NF-κB) 및 mitogen-activated protein kinase(MAPK)와 같은 다양한 신호전달 경로에 의해 조절된다41-43). 이 중 MAPK는 extracellular signal–regulated kinase(ERK), c-Jun amino-terminal kinase(JNK), p38 MAPK 3개의 서브유닛으로 분류되고 인산화 및 활성화되어 세포의 증식과 분화, 세포사멸, 대사 및 전사 과정을 포함한 다양한 세포 반응에 관여한다44). 꾸지뽕나무 잎과 우슬 복합물은 200 ug/ml 이하의 농도에서 대식세포에 대한 독성이 나타나지 않았으며, 염증반응을 유도하는 NO 생성량을 유의적이고 농도의존적으로 감소시켰다(Fig. 1C, 4). 또한 염증성 유전자들 발현량 역시 유의적이고 농도의존적인 감소를 나타내었으며, 이들의 발현을 조절하는 상위단계인 MAPK 발현량은 ERK를 제외한 JNK와 p38에서 유의적이고 농도의존적인 감소가 나타났다(Fig. 5, 6).

본 연구에서는 꾸지뽕나무 잎과 우슬 복합물에 대한 조골세포와 파골세포의 증식 및 분화에 대한 효능을 확인하고 in vitro 수준에서의 항염증 효능을 확인하고 구명하였으며, 이를 활용한 기능성 소재 개발에 대한 기초적인 자료를 제공하고자 한다. 또한 유의적인 결과를 바탕으로 다양한 골 관련 질환 및 염증성 질환에 대한 추가적인 연구의 발판을 마련하고자 한다.

결 론

꾸지뽕나무 잎과 우슬 복합물은 조골세포의 분화 및 활성화를 증가시키고 파골세포의 분화 및 활성화는 억제하여 골 대사에 대한 긍정적인 영향을 미칠 수 있으며, 이를 바탕으로 골 질환 예방에 효과가 있을 것이라 사료된다. 또한 염증 반응에서 MAPK 신호전달기전의 관련 단백질들의 인산화 억제를 통해 염증성 사이토카인의 유전자 발현량을 억제시키는 항염증 효능이 구명되었다. 결과적으로 본 연구에서 꾸지뽕나무 잎과 우슬 복합물이 골 질환을 예방하고 항염증 효과를 갖는 기능성 천연물 소재로써의 사용가능성을 제시하고 있다.

References

-

McNally EA, Schwarcz HP, Botton GA, Arsenault AL. A model for the ultrastructure of bone based on electron microscopy of ion-milled sections. PloS one. 2012;7(1):e29258.

[https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0029258]

-

Clarke B. Normal bone anatomy and physiology. Clinical journal of the American Society of Nephrology. 2008;3(Supplement 3):S131-S9.

[https://doi.org/10.2215/CJN.04151206]

-

Maruotti N, Corrado A, Cantatore FP. Osteoblast role in osteoarthritis pathogenesis. Journal of cellular physiology. 2017;232(11):2957-63.

[https://doi.org/10.1002/jcp.25969]

-

Zhang Y, Jordan JM. Epidemiology of osteoarthritis. Clinics in geriatric medicine. 2010;26(3):355-69.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cger.2010.03.001]

-

Kanis JA. Diagnosis of osteoporosis and assessment of fracture risk. The Lancet. 2002;359(9321):1929-36.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08761-5]

- Kang S-C, Lim J-D, Lee J-C, Park H-J, Kang N-S, Sohn E-H. Effects of fructus and semen from Rosa rugosa on osteoimmune cells. Korean Journal of Plant Resources. 2010;23(2):157-64.

- Joo I-H, Kim D-H. Effects of Yeonsan-Ogye Egg on MIA-induced Osteoarthritis Rat. The Korea Journal of Herbology. 2017;32(6):63-9.

-

Nelson HD, Humphrey LL, Nygren P, Teutsch SM, Allan JD. Postmenopausal hormone replacement therapy: scientific review. Jama. 2002;288(7):872-81.

[https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.288.7.872]

-

Yang KA, Saris D, Dhert W, Verbout A. Osteoarthritis of the knee: current treatment options and future directions. Current Orthopaedics. 2004;18(4):311-20.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cuor.2004.04.005]

-

Solomon DH, Shao M, Wolski K, Nissen S, Husni ME, Paynter N. Derivation and validation of a major toxicity risk score among nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drug users based on data from a randomized controlled trial. Arthritis & Rheumatology. 2019;71(8):1225-31.

[https://doi.org/10.1002/art.40870]

-

Chang SH, Jung EJ, Lim DG, Oyungerel B, Lim KI, Her E, et al. Anti‐inflammatory action of Cudrania tricuspidata on spleen cell and T lymphocyte proliferation. Journal of Pharmacy and Pharmacology. 2008;60(9):1221-6.

[https://doi.org/10.1211/jpp.60.9.0015]

-

Hiep NT, Kwon J, Kim D-W, Hong S, Guo Y, Hwang BY, et al. Neuroprotective constituents from the fruits of Maclura tricuspidata. Tetrahedron. 2017;73(19):2747-59.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tet.2017.03.064]

-

Kim D-W, Lee W-J, Asmelash Gebru Y, Choi H-S, Yeo S-H, Jeong Y-J, et al. Comparison of bioactive compounds and antioxidant activities of Maclura tricuspidata fruit extracts at different maturity stages. Molecules. 2019;24(3):567.

[https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules24030567]

-

Han XH, Hong SS, Jin Q, Li D, Kim H-K, Lee J, et al. Prenylated and benzylated flavonoids from the fruits of Cudrania tricuspidata. Journal of natural products. 2009;72(1):164-7.

[https://doi.org/10.1021/np800418j]

-

Hiep NT, Kwon J, Kim D-W, Hwang BY, Lee H-J, Mar W, et al. Isoflavones with neuroprotective activities from fruits of Cudrania tricuspidata. Phytochemistry. 2015;111:141-8.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.phytochem.2014.10.021]

-

Lee H, Ha H, Lee JK, Seo Cs, Lee Nh, Jung DY, et al. The fruits of Cudrania tricuspidata suppress development of atopic dermatitis in NC/Nga mice. Phytotherapy Research. 2012;26(4):594-9.

[https://doi.org/10.1002/ptr.3577]

-

Jo YH, Kim SB, Liu Q, Do S-G, Hwang BY, Lee MK. Comparison of pancreatic lipase inhibitory isoflavonoids from unripe and ripe fruits of Cudrania tricuspidata. PloS one. 2017;12(3):e0172069.

[https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0172069]

-

Jo YH, Choi K-M, Liu Q, Kim SB, Ji H-J, Kim M, et al. Anti-obesity effect of 6, 8-diprenylgenistein, an isoflavonoid of Cudrania tricuspidata fruits in high-fat diet-induced obese mice. Nutrients. 2015;7(12):10480-90.

[https://doi.org/10.3390/nu7125544]

-

Lee YJ, Kim S, Lee SJ, Ham I, Whang WK. Antioxidant activities of new flavonoids from Cudrania tricuspidata root bark. Archives of pharmacal research. 2009;32(2):195-200.

[https://doi.org/10.1007/s12272-009-1135-z]

-

Jeong G-S, Lee D-S, Kim Y-C. Cudratricusxanthone A from Cudrania tricuspidata suppresses pro-inflammatory mediators through expression of anti-inflammatory heme oxygenase-1 in RAW264. 7 macrophages. International Immunopharmacology. 2009;9(2):241-6.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intimp.2008.11.008]

-

Park KH, Park Y-D, Han J-M, Im K-R, Lee BW, Jeong IY, et al. Anti-atherosclerotic and anti-inflammatory activities of catecholic xanthones and flavonoids isolated from Cudrania tricuspidata. Bioorganic & medicinal chemistry letters. 2006;16(21):5580-3.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bmcl.2006.08.032]

-

Kim O-K, Nam D-E, Jun W, Lee J. Cudrania tricuspidata water extract improved obesity-induced hepatic insulin resistance in db/db mice by suppressing ER stress and inflammation. Food & nutrition research. 2015;59(1):29165.

[https://doi.org/10.3402/fnr.v59.29165]

-

Song S-H, Ki SH, Park D-H, Moon H-S, Lee C-D, Yoon I-S, et al. Quantitative analysis, extraction optimization, and biological evaluation of Cudrania tricuspidata leaf and fruit extracts. Molecules. 2017;22(9):1489.

[https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules22091489]

-

Park J, Kim I. Effects of dietary Achyranthes japonica extract supplementation on the growth performance, total tract digestibility, cecal microflora, excreta noxious gas emission, and meat quality of broiler chickens. Poultry science. 2020;99(1):463-70.

[https://doi.org/10.3382/ps/pez533]

-

Lee S-G, Lee E-J, Park W-D, Kim J-B, Kim E-O, Choi S-W. Anti-inflammatory and anti-osteoarthritis effects of fermented Achyranthes japonica Nakai. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 2012;142(3):634-41.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jep.2012.05.020]

-

Al-Mijan M, Park H, Lee Y, Lim B. Evaluation of the antioxidant and anti-inflammatory potential of fermented Achyranthes japonica Nakai extract. Nat Prod Chem Res. 2018;6:337-43.

[https://doi.org/10.4172/2329-6836.1000337]

- Jung S-M, Choi S-I, Park S-M, Heo T-R. Antimicrobial effect of Achyranthes japonica Nakai extracts against Clostridium difficile. Korean Journal of Food Science and Technology. 2007;39(5):564-8.

- Kim C-S, Park Y-K. The therapeutic effect of Achyranthis Radix on the collagen-induced arthritis in mice. The Korea Journal of Herbology. 2010;25(4):129-35.

-

Bang SY, Kim J-H, Kim H-Y, Lee YJ, Park SY, Lee SJ, et al. Achyranthes japonica exhibits anti-inflammatory effect via NF-κB suppression and HO-1 induction in macrophages. Journal of ethnopharmacology. 2012;144(1):109-17.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jep.2012.08.037]

- Iqbal Z, Shah Y, Ahmad L. Evaluation of anti-inflammatory activity of selected medicinal plants of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan. Pak J Pharm Sci. 2014;27(2):365-8.

-

Jang G-Y, Kim H-Y, Lee S-H, Kang Y-R, Hwang I-G, Woo K-S, et al. Effects of heat treatment and extraction method on antioxidant activity of several medicinal plants. Journal of the Korean society of food science and nutrition. 2012;41(7):914-20.

[https://doi.org/10.3746/jkfn.2012.41.7.914]

-

Yin X, Zhou C, Li J, Liu R, Shi B, Yuan Q, et al. Autophagy in bone homeostasis and the onset of osteoporosis. Bone research. 2019;7(1):1-16.

[https://doi.org/10.1038/s41413-019-0058-7]

-

Epsley S, Tadros S, Farid A, Kargilis D, Mehta S, Rajapakse CS. The Effect of Inflammation on Bone. Frontiers in Physiology. 2021;11(1695).

[https://doi.org/10.3389/fphys.2020.511799]

-

Ryu J, Kim HJ, Chang EJ, Huang H, Banno Y, Kim HH. Sphingosine 1‐phosphate as a regulator of osteoclast differentiation and osteoclast–osteoblast coupling. The EMBO journal. 2006;25(24):5840-51.

[https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.emboj.7601430]

-

Rodríguez-Carballo E, Gámez B, Ventura F. p38 MAPK signaling in osteoblast differentiation. Frontiers in cell and developmental biology. 2016;4:40.

[https://doi.org/10.3389/fcell.2016.00040]

-

Jeon M-H, Kim M-H. Effect of Hijikia fusiforme fractions on proliferation and differentiation in osteoblastic MC3T3-E1 cells. Journal of life science. 2011;21(2):300-8.

[https://doi.org/10.5352/JLS.2011.21.2.300]

- Seo M, Baek M, Lee JH, Lee HJ, Kim I-W, Kim SY, et al. Osteoblastogenic activity of Tenebrio molitor larvae oil on the MG-63 osteoblastic cell. Journal of Life Science. 2019;29(9):1027-33.

-

Owen R, Reilly GC. In vitro models of bone remodelling and associated disorders. Frontiers in bioengineering and biotechnology. 2018;6:134.

[https://doi.org/10.3389/fbioe.2018.00134]

-

Boyle WJ, Simonet WS, Lacey DL. Osteoclast differentiation and activation. Nature. 2003;423(6937):337-42.

[https://doi.org/10.1038/nature01658]

- Lee A-S, Jang S-J. Effect of Myricetin in Osteoclast Differentiation and Bone Resorption. Journal of Physiology & Pathology in Korean Medicine. 2010;24(1):74-9.

-

Moens U, Kostenko S, Sveinbjørnsson B. The role of mitogen-activated protein kinase-activated protein kinases (MAPKAPKs) in inflammation. Genes. 2013;4(2):101-33.

[https://doi.org/10.3390/genes4020101]

-

Newton K, Dixit VM. Signaling in innate immunity and inflammation. Cold Spring Harbor perspectives in biology. 2012;4(3):a006049.

[https://doi.org/10.1101/cshperspect.a006049]

-

Kyriakis JM, Avruch J. Mammalian MAPK signal transduction pathways activated by stress and inflammation: a 10-year update. Physiological reviews. 2012;92(2):689-737.

[https://doi.org/10.1152/physrev.00028.2011]

-

Johnson GL, Lapadat R. Mitogen-activated protein kinase pathways mediated by ERK, JNK, and p38 protein kinases. Science. 2002;298(5600):1911-2.

[https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1072682]